- Home

- Jürgen Fauth

Kino

Kino Read online

PRAISE FOR KINO

“Kino is a fast, complex, exhilarating roadster ride through history and time, a mystery, a documentary, a remarkable remix of reality and imagination. It is the story of a woman who becomes obsessed with her grandfather, a visionary film director in the Germany of the nineteen-twenties through World War II. Tracing the arc of his spectacular decline, she risks a husband and her ordinary life, but uncovers the powerful bindings of family, the sweet, dark loam of loss, and the instant-on high-voltage current of pulp fascism, dirty pictures, propaganda, cultural piracy, art and money.

It's quick but complicated, feverish, trying, speculative, high-minded, and occasionally Goebbels-esque. Everything forced into close and incendiary quarters. Kino is intoxicating Euro-brew, written with enormous skill and dedication.”

– Frederick Barthelme, author of Elroy Nights

“Jürgen Fauth's deft mashup of genre and historical period is both a full-throttle literary thriller of ideas and a contemplative examination of film and fascism. Kino is a debut of great intellectual force.”

– Teddy Wayne, author of Kapitoil

“A delirious melange of conspiracy, magic, sex, history, bad behavior, and cinema, Kino is a stellar entertainment, and Jürgen Fauth is a writer of rare, sinister imagination.”

– Owen King, author of Reenactment

“A surprising alternative history. Kino brings the golden age of German cinema to light with loving, sometimes gritty, detail and great precision.”

– Neal Pollack, author of Jewball

“A light-hearted romp that leads straight into darkness and back through the shadows on the wall.”

– Ben Loory, author of Stories for Nighttime and Some for the Day

“This is an elegant book, wrapping the core of a thriller in ideas that play with literary and semiotic conventions…Jürgen Fauth has a confident touch and is worth watching in the future.”

– David Marshall, Thinking About Books

“Movie nuts, arise! A happy and felicitous debut.”

– Terese Svoboda, author of Bohemian Girl

“While art may cause mental anguish and distress, ultimately it brings to light the true nature of our existence. That is the brilliance of art, and that is the brilliance of Kino.”

– Trip Starkey, The Literary Man

“Part historical fiction, part page-turning thriller, Kino is a well-told tale written by someone who exudes confidence on every page. Readers are in good hands with Fauth as he masters his realm, creating a world that is wholly his own yet accurate of a past era. His examination of both art's role in society and the portraits of 1920s Germany is worth the read alone.”

– Patrick Trotti, jmww

An Atticus Trade Paperback Original

Atticus Books LLC

3766 Howard Avenue, Suite 202

Kensington MD 20895

http://atticusbooksonline.com

Copyright © 2012 by Jürgen Fauth. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

ISBN-13: 978-0-9832080-7-5

ISBN-10: 0-9832080-7-7

Typeset in Palantino

Cover design by Jamie Keenan

“Art is free. However, it must conform to certain norms.”

Joseph Goebbels

Hotel Kaiserhof, Berlin

March 28, 1933

Chapter 1

Mina stumbled and fell headlong into her apartment, smacking her knees and the palms of her hands on the hardwood floor. She bit her lip, cursed, resisted the temptation to cry. Rubbing her bruised joints, she turned to see what had tripped her.

Just inside the door sat a pair of metal cases, knee-high, octagonal, green-grey, a sticker centered on each with Mina's name, unabbreviated, the way nobody ever used it. The label was handwritten in blocky capitals, with a peculiar choice of preposition that made the canisters seem more like presents than parcels: FOR WILHELMINA KOBLITZ.

Mina sighed. She reached for the keys and mail she'd dropped and picked herself up. She had spent the entire day at NYU hospital, where her husband Sam was ill with dengue fever. He'd caught the tropical disease on their honeymoon, which they'd cut short immediately after the resort doctor in Punta Cana diagnosed him. “Bad luck,” the doctor had said. The disease wasn't exactly rare, but there also hadn't been an outbreak in years.

They'd been back for three days now and the marriage was off to a rocky start. The reception had been a disaster, the honeymoon was ruined, and Mina was beginning to resent the long hours at the hospital. This was not how she had envisioned her new life. She spent as much time with Sam as she could, reading in the uncomfortable plastic chair under the glare of the fluorescent lights while her new husband tossed and turned, his eyes glassy, moaning and sweating through his pajamas. In his brief lucid moments Sam complained about the pain in his limbs, the heat, the all-too-real nightmares. Even when he slept, the moaning didn't stop.

Dengue fever could be fatal, but the smug New York doctor had assured Mina that Sam would be fine. He told her to go home. It could be another week before the fever subsided, and she should take care of herself, rest. Mina thought the doctor was too eager to touch her arm. She was attractive, a little short, but busty. Men tended to underestimate her.

The Greenpoint one-bedroom seemed smaller to Mina than ever. They had lived together for almost a year before getting married, and now the apartment was a mess, every open space crowded with wedding gifts–blenders, toasters, sheets, and silverware. The kitchen counter was covered with unopened mail. She hadn't unpacked their suitcases yet.

FOR WILHELMINA KOBLITZ.

Belated wedding presents from a distant relative? The last time she'd heard her full name had been at her college graduation, almost four years ago.

Mina pushed aside a stack of magazines and lifted the canisters onto the kitchen counter. Picking one at random, she popped its twin latches and opened the lid. Inside were four reels of film.

She opened the second container. Three more reels, kept in place by a jammed-in Styrofoam wedge. Sturdy plastic held black celluloid wrapped around the center. Wasn't this stuff flammable? Mina pulled a reel out of the case. She set it on the counter and wheeled it around until she found the end of the film strip, locked down with a pin that held the sprocket holes in place. She carefully unwound it, thinking how odd it was that even though her grandfather had been a filmmaker, she'd never held celluloid before.

Oh, she thought.

Did this have anything to do with her grandfather?

Mina had never known the old man, a German director who had emigrated to America during the Second World War. He'd made one big flop in Hollywood that still showed sometimes on late-night cable. All his German movies had been lost, and he'd killed himself before Mina was born. Her father refused to talk about him.

The celluloid in her hands was entirely black, and Mina kept unrolling it, unable to stop. She tried to wrap it around the fingers of one hand and turn the reel with the other, but the film kept slipping off. She let it stack up on the counter into a loose loop that curled on its own. After two more revolutions she hit a logo, something like a coat of arms. Then, white words on black: the credits. She held the film up to the neon kitchen light, but the letters were too small to read. She kept unwinding it further, and some of the celluloid slipped off the counter and onto the Swiss espresso mac

hine they'd gotten from Sam's boss. The words grew bigger until there were only two lines, and now she could make out letters, repeated on every advancing frame:

EIN FILM VON

KLAUS KOBLITZ

Into the empty apartment's silence, Mina made a surprised noise not unlike her husband's feverish moans. She was holding in her hands one of her grandfather's lost films.

Chapter 2

From: [email protected]

Date: Saturday, May 10, 2003

To: [email protected]

Subject: Please Don't Hate Me

Oh baby. I want you to know how horrible it felt leaving you in that hospital bed this morning. Your doctor assured me that the worst was behind you, and I'll be back in three days. I promise. We set up a screening for Sunday, and then I'm flying right back to you. I tried to explain, but you seemed pretty far gone and I don't know if you caught any of it.

I came home last night to what looks like one of the movies my grandfather made in Germany before the war. There were no stamps and when I asked Mr. Palomino who'd brought it, he shrugged. A “messenger boy” who'd made sure he put them inside the apartment. I talked to somebody at the Museum of the Moving Image, and she gave me a number at UCLA and I ended up talking to a guy at the Kinemathek in Berlin, Dr. Hanno something-or-other. He had the worst accent and he was rude, too. I'd forgotten about the time difference and woke him up. But you should have heard him when I mentioned my grandfather's name. Suddenly I was royalty. He asked me all kinds of questions about the film, the condition it's in, the reels, the cans–apparently they're called “cans”–and he asked me to measure the width of the celluloid, and how far from one sprocket hole to the next. He got really worked up. He thinks it's The Tulip Thief, my grandfather's first film, made in 1927.

That's a big deal if it's true, Sam. All of his German movies were lost, or at least that's what we thought, and suddenly, there's one sitting in the hallway of our apartment in Greenpoint. I asked how much it'd be worth, but he didn't want to say.

Now here's the thing: it's an old kind of negative, and it's in a weird format, something called Doppelnockenverfahren. It's like the Betamax of film. You need special equipment to show it, and the only remaining projector that can handle it is in Berlin at this film museum.

You see? I feel like shit for leaving you and coming over here, but I hope you understand. If this is for real, it's worth a *lot* of money. Maybe enough for a brownstone with a little garden where we can drink our coffee outside. I could pay off my student loans. Lucy and Josh promised they'd come and visit you every day. I haven't told my parents–my Dad's probably still mad about the wedding, and grandfather is a touchy subject with him anyway. Well, I guess everything's a touchy subject with him.

I left in such a hurry this morning, Sam, I simply grabbed my suitcase from the trip. I hadn't unpacked yet, so why not just take it, right? Wrong. It's fucking cold here and I don't even have a coat or a pair of warm shoes. Instead, I have three bathing suits, my mask and snorkel, and a pair of fucking flippers. I'm such an idiot. I guess it's all been a little much. I don't even speak German. Getting here was awful, too: they made me take off my shoes again at security, and there were five babies on the plane. I counted. Five. I took a Xanax and drank some wine but there was no way I could sleep. My mind kept spinning. Now I'm completely whacked and it's not even noon. Technically, we're still on our honeymoon. We should be making love in the honeymoon suite, drinking piña coladas, and snorkeling in the clear blue water.

Get better quick. Call me.

I love you,

Mina

Chapter 3

The man from the film museum, Dr. Hanno, walked into the hotel lobby at precisely five p.m. Seventeen o'clock, he had called it on the phone. He was younger than Mina had expected, handsome, barely thirty. He had short blond hair, wore rimless glasses, and carried a leather backpack over one shoulder. His last name was Broddenbuck, and when he said it he eyed Mina conspicuously as if he expected her to make a joke. She didn't know what was funny and just looked back at him blankly.

Mina was wearing a cotton skirt, T-shirt and a denim jacket, and right away, she went into a monologue to explain her unseasonable outfit–the aborted honeymoon, the dengue fever, her cluttered apartment, the reels, and the suitcase, the stupid suitcase she didn't think to repack.

“Until I can shop for warmer clothes,” she said, suddenly worried that she was speaking too fast for the German. His expression was blank. “Is it okay if we stay here? If this lobby's no good, we could go up to my room?”

Dr. Hanno lowered his eyes and fidgeted with the car keys in his hands. He was flustered.

“Oh, I am sorry,” Mina said. “No funny business–I'm happily married.” She wiggled the fingers of her newly-ringed left hand at him, but that only made matters worse.

“Frau Koblitz,” he said with a stilted German accent. “I made reservations at a restaurant. We were going to have dinner and talk about your grandfather, no?”

Mina sighed. Flexible this guy wasn't. There was a cool draft and she was getting impatient. In fact, she was freezing cold standing in the damn hotel lobby. Outside, Germany seemed impossibly cold and gray. She didn't know what she was doing here, when she was supposed to be with Sam. “Isn't there anything we can order in? If you come upstairs, you can take a look at the movie.”

Dr. Hanno's confidence returned at the mention of the movie. “Yes,” he said. “With pleasure. Do you like Turkish food? I could pick up something and return?” Mina grinned her best grin. She could take control of the situation.

“Meet me upstairs,” she said and gave him the room number.

He came knocking on her door with food, two fat triangular sandwiches wrapped in aluminum foil that reeked of garlic.

“I've never eaten one of these before.” Mina sat on the edge of her double bed, unmade and still warm from her jetlagged afternoon nap. Dr. Hanno sat in the narrow chair by the coffee table next to the window. Mina was hungry. The shredded lamb was delicious.

“My mother doesn't approve, but I live on Döner,” he said, watching her eat. She had not waited for him. “Don't you have Turks in New York?”

“I grew up in Connecticut.”

Dr. Hanno gave her a blank look. He cleared his throat. “So you brought…” Döner in hand, he eyed the room. On the floor by the bed, next to the opened suitcase spilling T-shirts, beach towels, and a pair of flip-flops, sat the two metal containers. “Ah!” he said. “Jawoll! May I?”

Mina nodded, wiping a smear of yogurt sauce from her face. Dr. Hanno, who was already hoisting the cans onto the table, amused her. With quick, familiar movements, he unlatched them and removed the first reel. He threaded the celluloid through his fingers with studied precision and held it up against the light.

Mina had no patience. “Is it real?”

Without taking his eyes off the film, Dr. Hanno slowly nodded. “Naturally, we'd have to run some tests in the lab, but just from looking at it, I can tell you that film in this format hasn't been produced in over sixty years. It's a nitrate print that shows clear signs of advanced age. We won't be able to know about wear and tear, possible damage, missing parts, and so on, until we've looked at it more thoroughly. From what I can tell, it's astoundingly well-preserved. Dirt, dust, scratches, and tears seem to be minimal, and it doesn't look like there has been much shrinkage or fade.”

Now he took his eyes off the film to look at her. “Do you understand what this means? The value is incalculable.”

“I like the sound of that,” Mina said. “I've got staggering student loans to pay off.” The truth was she thought that she'd exaggerated the worth of the movie in her email to Sam. How many people were really buying DVDs of seventy-five-year-old silent films? Sam had a high-paying job as a game designer and insisted that he didn't mind paying off her debt–but she felt like an idiot for ever starting law school in the first place. She had been trying, she figured out only after dropping out, to pl

ease her father.

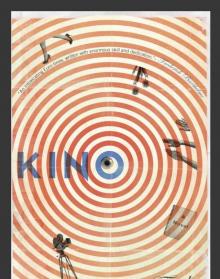

Dr. Hanno looked at her as if she were speaking a language he didn't understand. “I wasn't talking about money. I am talking about cinema. Preservation, the cultural heritage of the tenth art! I am not talking about money. I am talking about Kino!”

Dr. Hanno kept surprising Mina. She understood he loved movies, but this sudden fervor was intimidating. Clearly, he was a man who wouldn't have hesitated for a second before leaving a feverish lover behind in a hospital room in order to watch a movie. What was her excuse?

“Kino,” Mina repeated.

Dr. Hanno smiled. “It was your grandfather's nickname, before the war. The Wunderkind of Neubabelsberg. Everybody called him Kino.”

“Oh. It means the movies, right?”

“Yes, from Kinematographie. You didn't know?”

Mina felt herself getting defensive. “My father doesn't talk about him.”

“You know about his suicide, and that he made films for the Nazis, and about his leg, yes?” He had cooled down again and carefully rewound the reel and closed the can's latches.

“His what?”

Dr. Hanno held his head sideways. “His peg leg. He was missing a leg, below the knee. A childhood accident. Surely you must know this?”

Mina thought of photographs she'd seen, but she couldn't remember any of them showing her grandfather below the belt. Was it possible? What else didn't she know? Mina felt something like vertigo.

“Please, tell me,” Dr. Hanno asked, “What do you know?”

Mina shrugged. “It's not like he was really famous. He made a pirate movie in Hollywood and it flopped. All his old movies were lost. He killed himself before I was born. My father thinks he's an embarrassment.”

“Well,” Dr. Hanno said. “In film histories, he is usually considered a ‘minor émigré filmmaker,’ but he was a real auteur, avant le mot. An encyclopedia entry will tell you that he was born in Königstein near Frankfurt in 1903 as the son of an industrialist, and that his 1927 debut Tulpendiebe made him the youngest writer and director in the history of Ufa studios. Marriage the same year, eight more movies in Germany, five of them during the Third Reich.”

Kino

Kino